The life, death, and rebirth of moderate-density apartment buildings in Chicago

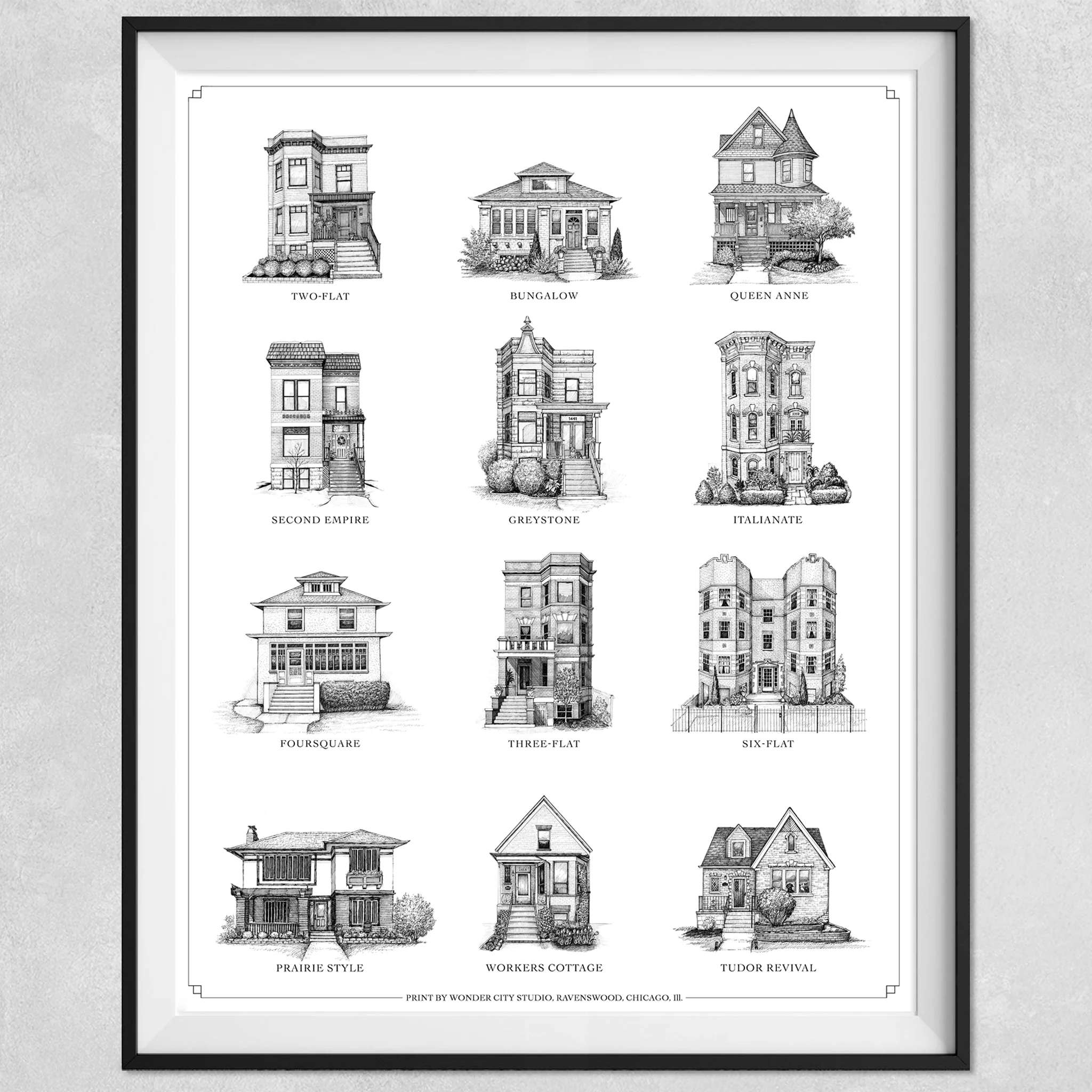

The pantheon of Chicago architecture tends to cluster at either end of the density spectrum. In one corner you have the trophy commercial skyscrapers; in the other you have icons of domesticity, the bungalow and Chicago's answer to the East Coast rowhome, the stacked flat.

But Chicago does have a tradition of neighborhood-scale apartment buildings that allow for more people, and more household type diversity, than these latter buildings. (Few units in single-family homes or stacked flats have fewer than two bedrooms.) That tradition, however, was interrupted for about half a century between 1971 and 2022; while stacked flats have been built regularly during periods of economic expansion more or less consistently from the late 1800s through the present day, new construction of moderate-density apartment buildings only resumed with the passage of the Connected Communities ordinance and the reduction of parking requirements in some residential zones.

For the purposes of this post, I'll stylize these apartments into three categories: Courtyard buildings (1900-1957); Four plus ones (1961-1971); and Contemporary (2022-present).

Courtyard buildings (1902-1957)

Despite being B-list celebrities of Chicago architecture, there are some excellent resources on courtyard buildings, which I won't try to extensively summarize or reproduce here.

But, briefly, courtyard buildings began to make an appearance after the 1902 Tenement Law, which, two decades before the city's first zoning code, mandated some minimum quality standards for new apartment buildings. Among other things, this included windows in every room, and leaving at least 35% of the lot as open space.

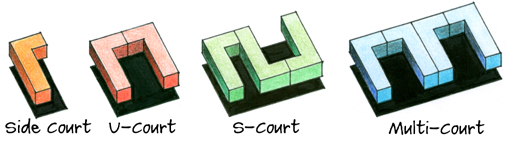

As Larry Shure has pointed out, courtyard buildings are really the result of combining a modular form designed to accommodate this requirement: the L-shaped block.

The L-shaped block accommodates the window and open space requirements while also accomplishing a few other things, notably 1) allowing apartments to be clustered around a series of separate entryways, avoiding the need for an internal hallway running through the building that would take space away from the apartments; and 2) adapting to Chicago's very deep blocks by orienting the building perpendicular to the street, avoiding dark rooms in the middle of the building without "wasting" land at the front or back of the lot.

Although courtyard buildings, like three flats, are typically 3.5 stories, they are meaningfully higher-density, because of this perpendicular orientation. Where a three flat is, definitionally, three units on a single 25' by 125' lot, courtyard buildings typically have 24 to 40 units over four lots, or six to 10 units per lot. This density is a major part of why courtyard-heavy neighborhoods like Rogers Park or South Shore have among the highest population densities of any Chicago communities. Courtyard buildings also tend to offer a range of unit types, with apartments facing the street often having two or three bedrooms while apartments at the rear of the building often have one bedroom.

While courtyard buildings are typically thought of as a prewar typology, that is not entirely true. The Great Depression and World War II created a roughly two-decade pause on construction, but courtyard buildings were built again in the early postwar period until about 1957.

Postwar courtyard buildings in many respects look like streamlined prewar buildings, but looked at from above you can see what makes them different. Hint: It's in the back.

In 1942, Chicago passed its first major zoning revision since the original 1923 code. While in many ways the 1942 code was relatively friendly to higher-density development, it took the momentous step of introducing the city's first off-street parking requirements, mandating one parking spot for every three apartments. Where prewar courtyard buildings were able to maximize the size of their courtyards and their square footage by reaching all the way to the rear lot line, postwar courtyards had to make room for cars to park behind the building off the alley.

Still, at one spot per three apartments—and with three parking spots fitting snugly side by side on a 25' wide lot—courtyard buildings could accommodate up to nine apartments per 25' by 125' lot, well within their typical density.

Four plus ones (1961-1971)

This arrangement would not last long, however, because in 1957 Chicago significantly revised its zoning code again. The 1957 code was the first to really lean into the trend of postwar suburbanization, and made a number of consequential changes, including the outlawing of coach houses and elimination of many side street businesses. But for the purposes of this post, its most consequential change was to increase off-street parking requirements from one space per three apartments to one space per two apartments.

At this ratio, most courtyard buildings were no longer feasible from a purely geometric perspective: There was not enough room to fit the number of cars required, even where the zoning code theoretically permitted courtyard-level density. After nearly six decades of service, courtyard buildings had been functionally outlawed.

In their place, developers invented the "four plus one." If a key innovation of the courtyard building was the horizontal arrangement of the L-block, the key innovation of the four plus one was the vertical arrangement of a quasi-submerged full level of parking underneath four floors of apartments. Only by reserving an entire floor of the building for parking could the 1957 requirements be satisfied.

If courtyard buildings are B-list celebrities, four plus ones are, for a lot of people, villains. The need for a full floor of parking meant that four plus ones eliminated the landscaped courtyard facing the street in favor of a boxy facade with smaller internal openings for light and air. This arrangement also made it impossible to keep the courtyard buildings' separate entryways for columns of apartments, requiring a single central corridor and placing smaller apartments on either side of it, reducing light and cross-ventilation. On the other side of the ledger, however, most four plus ones did feature elevators, which courtyard buildings essentially never had.

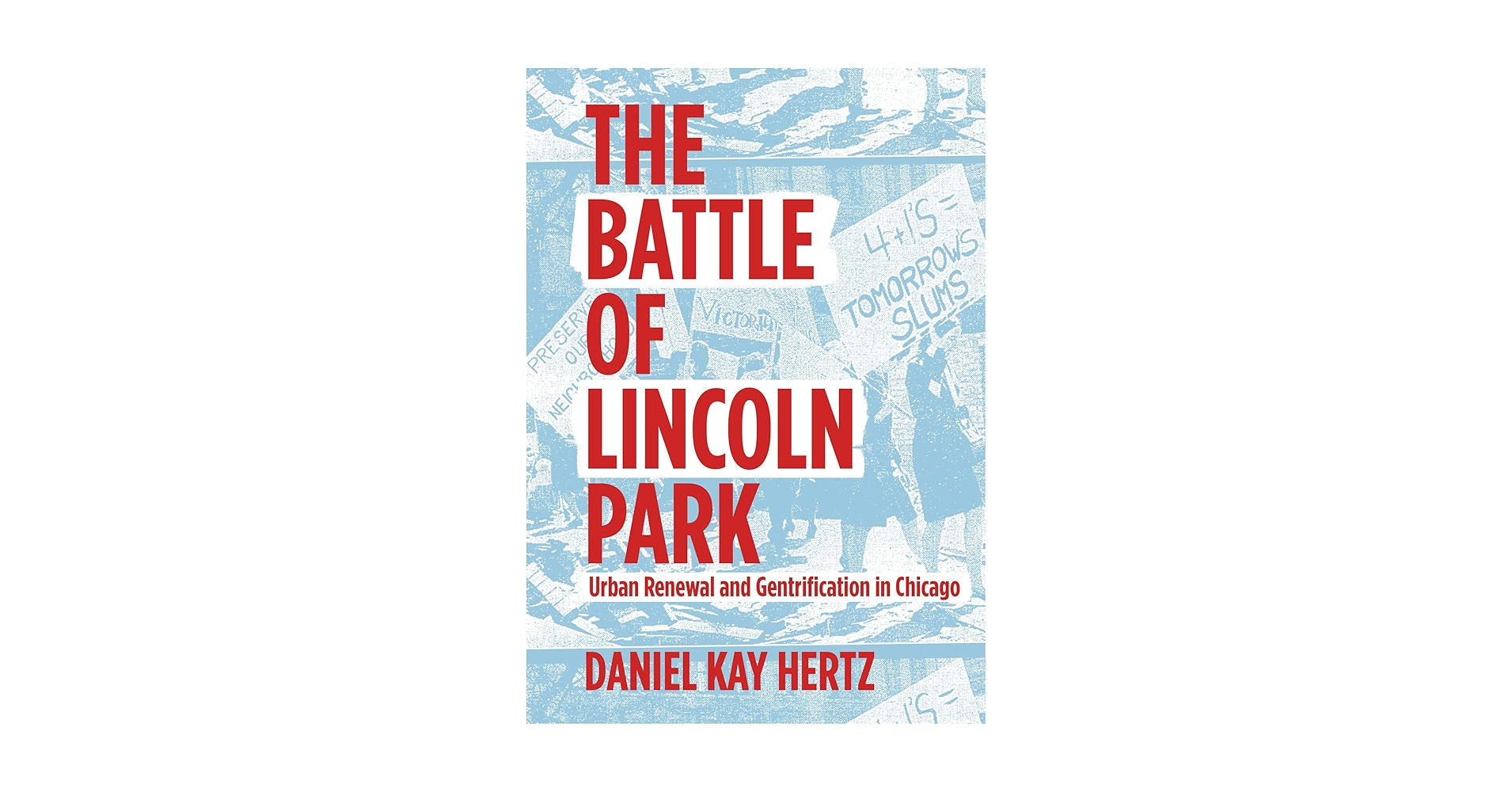

Four plus ones were nearly instantly reviled by their neighbors, mostly in higher-income areas on the north lakefront. My book has a brief passage on this, but the gist is that four plus ones were everything that the professionals who had newly discovered the romance and convenience of city living in places like Lincoln Park and Lakeview in the 1960s hated: They were too dense, too full of renters, and clashed too much with the Victorian aesthetic that the postwar rehabbers cherished.

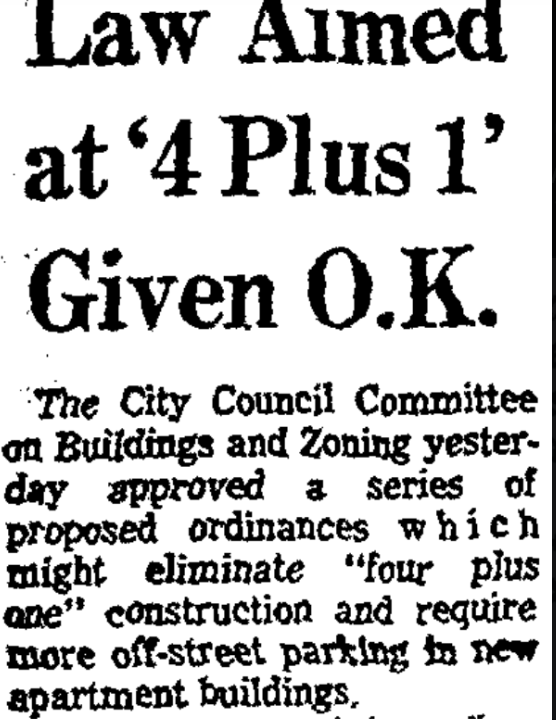

As a result, four plus ones were built at a breakneck pace for about a decade until 1971, when a campaign to eliminate them culminated in the passage of an ordinance in City Council that, among other things, established a one-for-one parking requirement for apartment buildings for the first time in the city's history.

At one parking space per apartment, even reserving a full floor for cars no longer allowed for the kind of density courtyard buildings and four plus ones had provided. For the next fifty years, Chicago essentially did not have a way to build at residential densities in between three flats and highrises.*

*The closest thing were the mixed-use midrises that became more common in the 2010s as parking requirements were loosened in business and commercial zones, particularly along the Milwaukee Avenue corridor. Nevertheless, these are a different beast: Almost always more than five stories, with ground floor storefronts, and constrained to arterial commercial streets. By contrast, courtyard buildings and four plus ones were definitively low-rise, fully residential, and side-street typologies.

:( (1971-2022)

:(

Contemporary (2022-present)

This half-century pause highlights one of the complexities, not to say absurdities, of the zoning code. At any point in this period, if you naively read the density tables in the code, you would have concluded that Chicago provided ample opportunity for moderate-density residential buildings. In 2021, for example, RM-5 zoning was plentiful along the north and south lakefronts, and inland in certain pockets on the West Side. According to the zoning tables, RM-5 allowed for something like eight apartments per standard 25' by 125' lot—well within courtyard range.

But this allowance was essentially vestigial. Because zoning codes apply multiple overlapping requirements—and because new construction must meet all of them—actually achieving that level of density while also providing the required number of parking spaces was impossible. In a sense, the density provisions of the zoning code were simply never updated to match the 1971 parking requirements.

But by the same token, that meant when the Connected Communities ordinance reversed the 1971 policy—dropping parking requirements for mid-density residential zones back to one for every two apartments, and creating an administrative path to eliminating off-street parking altogether—a meaningful amount of infill potential was created even though the ordinance did not actually change legally allowed density.

We are obviously only a few years into this new era—and the years have been weird ones, immediately following the Covid lockdowns and featuring rapid construction cost inflation and interest rate increases that have made all kinds of development difficult—but we are, already, seeing the effects of a return to pre-1971 parking policy.

One version is something like a 21st century four plus one: for example, this five-story building in Edgewater. While the street-facing side of the ground floor is lined with apartments, avoiding the garage and curb cut that makes four plus ones somewhat hostile to passersby, a view from the rear of the building shows that much of the first floor is in fact dedicated to parking, much like a four plus one. (This development did not use the administrative adjustment process to reduce its parking requirement below one space per two apartments; now that a 2025 ordinance has eliminated the need to use that process, it will be interesting to see whether developers choose to use it, or decide that their potential tenants/homebuyers want that much parking.) At 64 apartments, it has nearly nine units per standard city lot—right back in the courtyard building and four plus one range.

While we are likely to see more of these, they do require assembling multiple lots. In the 1960s, this was less of a problem, as many of the neighborhoods that were zoned to allow four plus ones still had a number of older, run-down single-family homes, which in the housing market of the time could be bought cheaply.

Today, single-family homes in places like eastern Lakeview and Edgewater are rarer and, where they exist, seven-figure affairs. The neighborhoods where the economics of land assembly are likeliest to work out are generally ones that are zoned to disallow anything denser than three flats—or, indeed, single-family homes.

As a result, Connected Communities might be more likely to unleash what Steven Vance has called the "6-3" or "8-3," in which six or eight units are built on a single lot while providing only the three parking spaces that fit on a rear pad facing the alley. While in many cases appearing as a bulky three-flat, these buildings can provide a homes-per-lot ratio comparable to courtyard buildings or four plus ones, and don't require land assembly.

So far, I have seen these permitted mostly in places like Edgewater and Bronzeville. They tend to appear fairly utilitarian, and are priced accordingly—not capital-A Affordable, but in the realm of 90-110% of Area Median Income, substantially below the typical cost of a condo in a new construction three flat in the same neighborhoods.

As in previous eras, developers are likely to continue to experiment with different ways to build under new rules—and the rules are likely to continuing changing periodically. But barring an unforeseen left turn, it does seem like the 1971 parking law marked the start of a time-bound era, rather than the permanent closing of a door to a workhouse housing typology in Chicago neighborhoods.