Why are LIHTC projects so expensive to build?

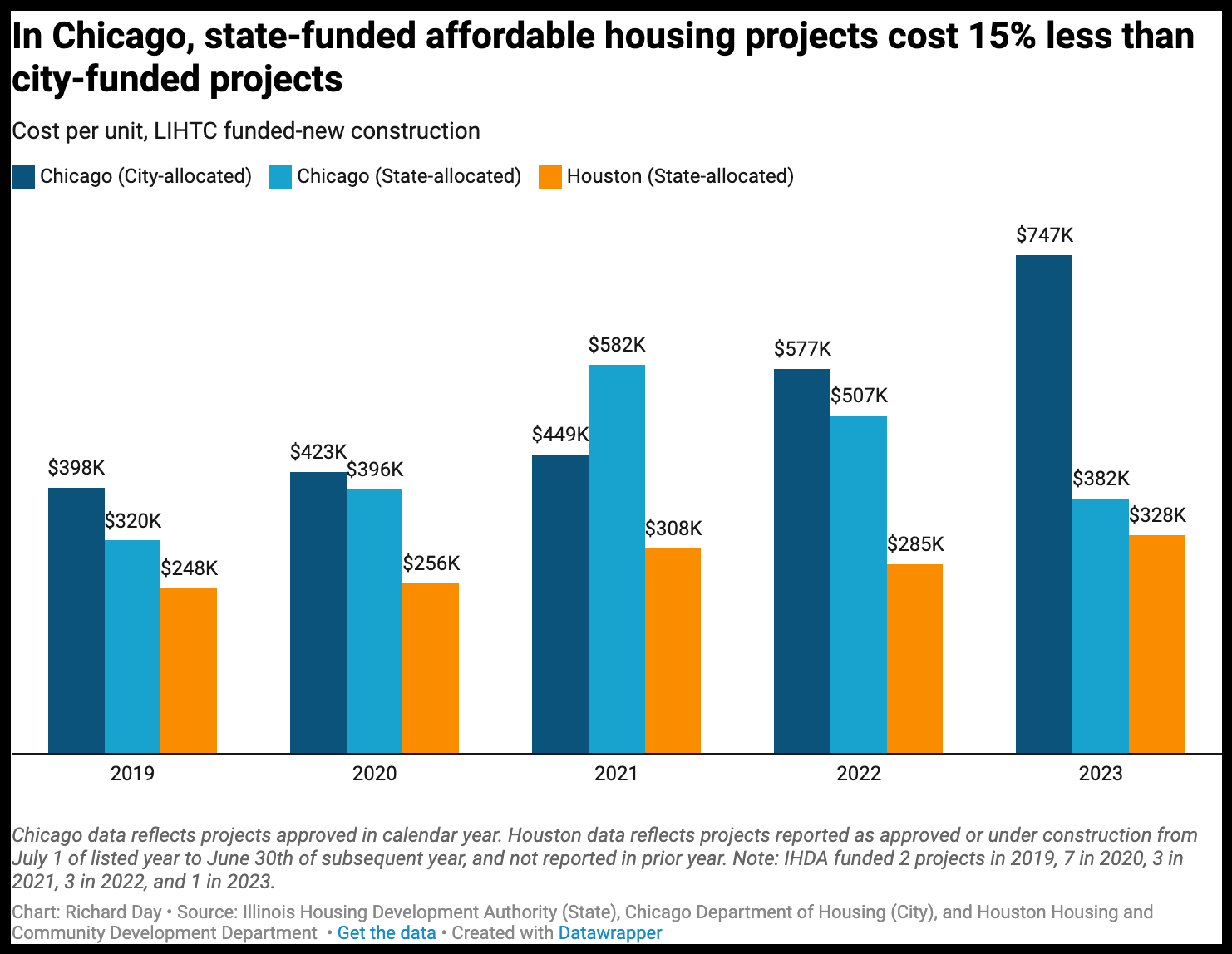

For at least a year, in certain very particular corners of LinkedIn, Substack, X, and Bluesky (along with the Crain's and Tribune editorial pages), affordable housing construction costs have been a hot topic in Chicago. It's easy enough to see why: The headline numbers are pretty shocking to those who haven't gotten used to them, with typical developments easily running into the $700,000s or $800,000s in costs per unit—figures that dwarf even luxury highrise construction by market rate firms (anecdotally, around $450,000 to $550,000), as well as more cookie-cutter, small-margin neighborhood multifamily development (anecdotally, perhaps around two-thirds of the luxury highrise figure).

On my own social media posts, I have criticized a lot of the discussion of these facts for being glib or confused. Over the weekend, after another viral reference to the issue (a single paragraph in a longer guest post at Matt Yglesias' newsletter), I was told, politely, that if I was going to continue to criticize I should probably offer my own interpretation of what's going on. Fair enough!

I should stipulate a few things up front:

- Construction costs are a real issue, in affordable housing as in transit and whatever else. While I have spent a lot of time working to get more resources for affordable housing, it's just true that at any level of funding you can do more if things cost less.

- Some of the public conversation about construction costs has been productive, whether or not you agree with all of it. A City That Works has emphasized the extent to which there are genuine policy tradeoffs between things we want and overall cost, an important thing to keep in mind regardless of where on the scale of those tradeoffs you think the City should land. People like Cat Vielma, who works in LIHTC finance in Illinois and other states, have been able to share real concrete examples of some of the issues that reduce efficiency.

- The City is aware of the issue and is actively working on it! The Department of Housing and other agencies have been engaging both on broad issues of development and LIHTC-specific issues via the Cut the Tape process for over a year with the goal of speeding development and reducing costs. (For clarity, I am not involved in any of these engagements.) This is not a situation where City Hall has its head in the sand—again, whether or not you agree with where they are landing on any given policy question.

With my throat cleared, let me now offer my analysis: I don't know exactly why costs have gone up so much. I think there is a reasonably long list of things that almost certainly are contributing to the problem, but I think getting beyond that point requires some actual serious technical research. We need, in other words, a Transit Costs Project for housing—"need" both because the answers aren't going to be found by casual reasoning from available data, and because it's actually a serious problem.

Still, we can get beyond some of the most blunt-instrument approaches to the problem by listing some of the known issues:

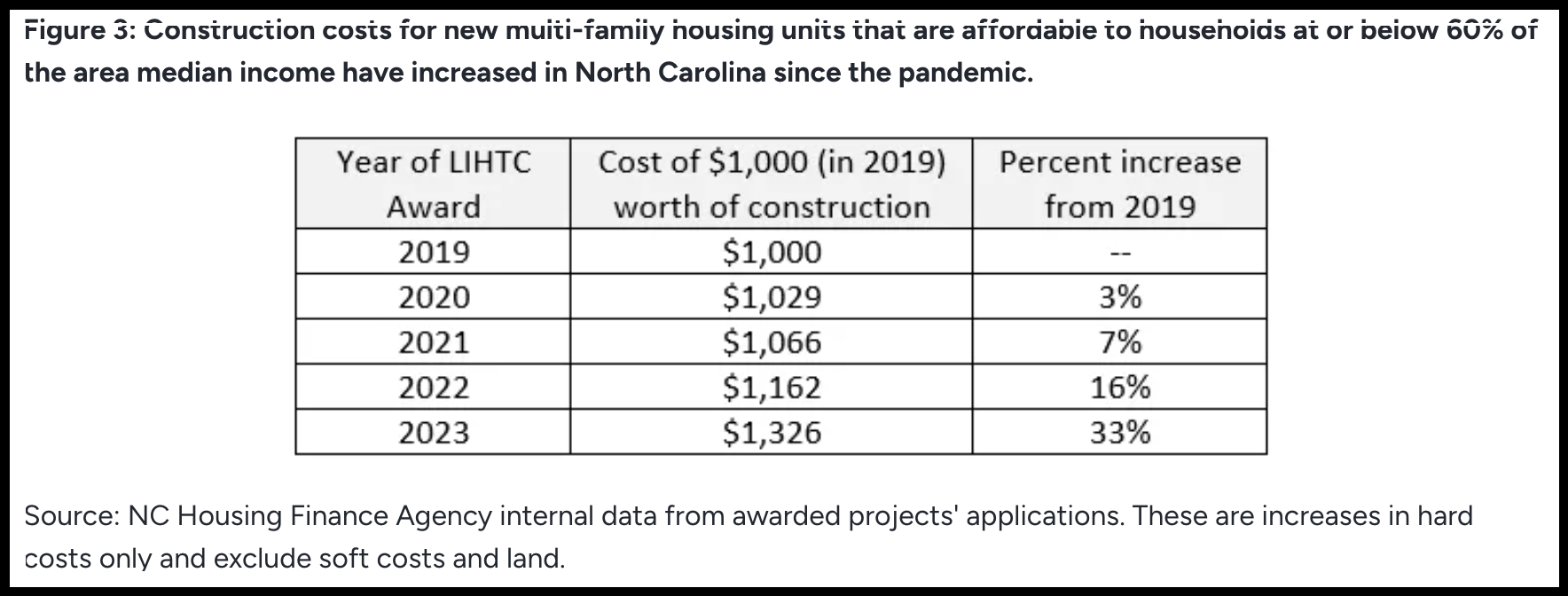

- Construction costs are up nationally since the start of the pandemic, by a lot. You can just Google things like "housing construction costs up" and come across a posts like this from North Carolina's Housing Finance Agency, showing that construction costs increased by a third in that state between 2019 and 2023. That obviously has nothing to do with anything the Chicago Department of Housing is doing, but DOH is facing the same headwinds.

- Affordable housing in Chicago is held to standards that market rate housing is not, and many of these standards have costs. In many cases, they are about achieving policy goals that most Chicagoans would find worthwhile: Paying construction workers a good wage, for example, or ensuring that firms owned by women and people of color aren't entirely shut out of publicly funded contracting. There's also just a layer of architectural and construction review that City-subsidized housing goes through that market rate housing doesn't have to; depending on your perspective, you might argue that's just creating more hoops to jump through or it's doing due diligence that's warranted when tens of millions of taxpayer dollars are on the line. In any case, these are policy choices about tradeoffs, and we give something up by saving money on these things; the A City That Works post focuses on this aspect of the issue.

- Affordable developers do not operate at the same scale as large market rate developers. This is true both at the property level, where those luxury highrises that cost less than LIHTC buildings to construct are typically 200-500 units, as opposed to 40-100; and at the firm level, where large market rate developers have a handful of properties going at any given time, while local LIHTC developers might build one every couple years. (There are probably a couple dozen affordable development firms active in Chicago; the City's once-every-two-years funding round generally makes 10-12 awards. You can do the math.) In each case, LIHTC developments don't have access to the economies of scale that larger market rate developments do.

- Affordable developers have much more complicated finances to work with than market rate developers. A typical market rate development—even one of those 200-500 unit behemoths—might only have a senior construction loan, an equity investor, and cash from the developer themselves. By contrast, LIHTC is designed to only cover 30-70% of the cost of construction of affordable housing; a wide variety of local funds typically need to be pulled in to fill the gap, from Community Development Block Grants to HOME Investment Partnership to TIF to bond funds to Illinois Donation Tax Credits to private grants from ComEd or philanthropy to etc, etc, etc. Each source comes with its own stack of compliance paperwork and legal and financial vetting. This dramatically increases "soft" construction costs (professional services not directly related to stacking bricks on top of one another) and extends the time it takes to go from approved proposal to breaking ground. This is a feature of LIHTC nationally; there are some things that can be done to help at the local level, such as creating more flexible pools of gap financing (this was a major reason for approving the Housing and Economic Development Bond), but it's not going to be resolved entirely without a federal overhaul of affordable housing funding.

- Speaking of which, affordable developments take a long time. This involves carrying costs, and during times of rapid construction cost inflation (like the 2020s) it means that costs can balloon from the time of LIHTC award to actual construction. Some of that is the financing stack; some of that is Chicago's approval processes, which for a given project might include:

- A year or more of public meetings to gather input and negotiate everything from the number of units to the height of the building to the size of the setbacks to the programming of the commercial units on the ground floor to whatever else you can think of.

- City Council votes to approve zoning in the Committee on Zoning and full Council.

- City Council votes to approve the financing package in the Committee on Finance and full Council.

- Zoning Board of Appeals votes to approve any required special use or variation.

- Zoning Administrator administrative review and approval of administrative adjustments.

- Chicago Plan Commission votes to approve a Planned Development designation, if necessary.

- Chicago Development Commission votes to approve any TIF funds used.

- And other administrative reviews regarding architectural plans, transportation demand management, and so on. MPC has a nice five-pager that gets into some (but not all!) of these details.

- City-funded projects have some challenging political dynamics with respect to cost control. Market-rate projects that see costs balloon from initial estimates can just fail, because they either lose their financing or their developers choose to walk away rather than lose money. But once an affordable development is announced, the City and local alder have a pretty strong incentive to make sure it gets built. Moreover, because even the best-performing affordable development cannot work financially without subsidy, there's no clear "breaking point" where what once pencilled no longer does. As a result, cost increases tend to just be "eaten" via additional subsidy.

- Being a City vendor is not fun. This is true whether you are building affordable housing, performing some kind of professional or social service, or whatever else you can think of. Reimbursements take forever; you have to fill out onerous disclosure forms; etc etc. Anecdotally, just the need to budget for carrying significant receivables from the City leads vendors to substantially upcharge when the City is the client, versus doing the same work for a private client.

This is not comprehensive, but you get the idea. If you want to get a sense of some of the other issues developers complain about, you can review the DOH, DPD, DOL, DOF, and other to-dos in the Cut the Tape progress tracker.

(A sample: "Eliminate the review of developer-GC contracts by the DOH Construction Compliance team. Instead, implement an affidavit indicating GC has sole responsibility for assuring compliance with ATS Manual." "Launch a working group to determine how to reduce the administrative burden of the City’s Economic Disclosure Statement (EDS)– exploring extending the expiration period, allowing exemptions for projects that receive an allocation of Low-Income Housing Tax Credits, and more." "Eliminate the minimum three-bid requirement for General Contractor on any DOH-funded rehabilitation project that are subject to ATS Manual, allowing the developer to select GC noncompetitively in order to include them earlier in the design process." These are pretty under the hood, but that's where the problem is.)

Before closing, I want to address a response that the cost issue sometimes provokes: Why not pivot to doing something else? How can this be the most efficient way to help people who need affordable housing?

A few thoughts on that:

- First, new purpose-built affordable housing accomplishes some things that other approaches, like acquiring market-rate buildings or providing rental subsidies directly to tenant households, cannot. The cheap rental buildings available on the market, for example, are almost certainly not accessible to people with mobility-related disabilities. Families with rental vouchers face massive barriers to actually using them, especially in higher-cost areas. In many disinvested neighborhoods, subsidized housing is the only way to add to the housing stock at all, because private developers can't get financing to build, often because market rents can't cover the cost of construction.

- To a great extent, this is a new problem. As recently as 2019, per A City That Works, the average cost of a Chicago LIHTC project was under $400,000 per unit, and in 2021 the average cost was still under $450,000; the eye-popping figures in 2023 represent a 30% increase in just one year over 2022. This means, first of all, that there has not been very long to identify the problem and get everyone on the same page that there is, in fact, a problem. Because DOH only does a LIHTC round every two years, 2025 will in fact be the first round since the scale of the issue has been what it currently is. Second, it means that there hasn't been very much time to try to address it. We don't yet know, in other words, how amenable this problem is to attempted solutions.

- Finally, on that last note, the City is in fact trying to address the issue. While the 2025 QAP does not represent a total overhaul from prior rounds, DOH did publish a memo outlining a number of changes it is making to the much-maligned Architectural and Technical Standards Manual (ATSM) for proposals submitted this year. Moreover, some real progress is being made on Cut the Tape items: zoning processes have been amended to consolidate multiple approvals into one; design review has been shortened dramatically; financial moves like restructuring or tax-exempt bond transfer have been made administrative, rather than requiring Council approval; and so on. There's a lot of room to do more, both on deep under-the-hood issues as well as name-brand ones like prerogative. (Though even on that there's progress, in the form of proactive rezonings of major corridors to allow the kinds of zoning designations that LIHTC and other multifamily developments need.)

Anyway, this is not the sort of thing where I have a grand proposal or conclusion to make. Affordable housing construction costs are a problem; their causes are many, and the relative importance of the causes need some deep analysis to tease apart; they're also a relatively new problem and we need some time to implement and evaluate the things the City is doing to try to address them; and yet we also need to maintain a sense of urgency because, again, it's a problem.