How to get deeper affordability: Capital versus rental subsidy

Moderate versus deep affordability

While we (advocates, elected officials, public agency staff, and media) often speak in a binary shorthand in which all housing is either "market rate" or "affordable," anyone who has actually paid rent knows that what is "affordable" entirely depends on how much money you have.

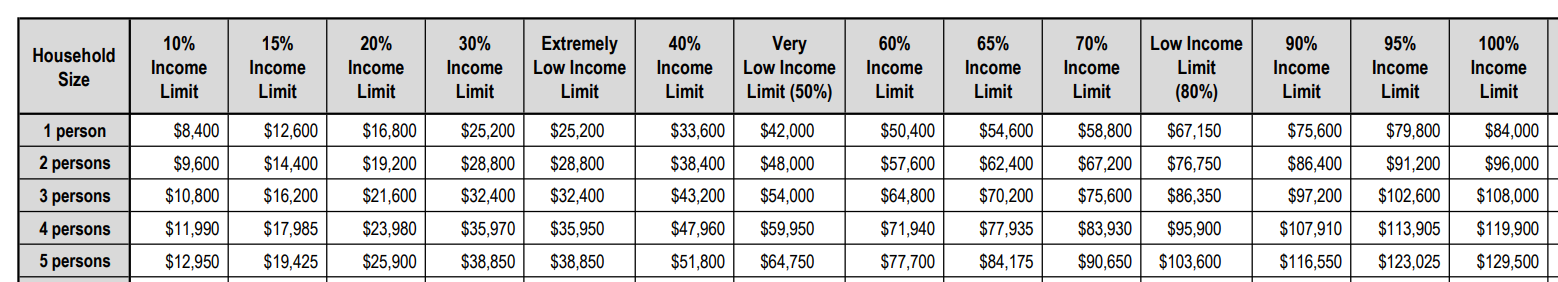

The scale that the federal government uses to measure affordability—and therefore the scale state and local governments also use, since they rely on federal resources—is called "Area Median Income," or "AMI." As in, "this apartment is affordable at 60% AMI," meaning: This apartment is affordable to a household making 60% of the median income in this metropolitan area.

(Two footnotes here, except I haven't figured out how to do real footnotes in Ghost yet. One, sometimes people will argue that the "area" should be calculated as a neighborhood, rather than the whole region, but this is why it's important to think of AMI as a scale, not a policy per se: It doesn't determine the actual dollar level of affordability any more than a table gets bigger if you measure it in centimeters rather than inches. What actually determines affordability—well, that's the subject of the rest of the post. Two, "affordable" is defined federally as 30% of a given household's income.)

Now, 60% AMI happens to be the default level of a lot of affordable rental housing—both the Low Income Housing Tax Credit and Chicago's Affordable Requirements Ordinance make that the required average in most developments. But as you can see above, 60% AMI does not describe a household in deep poverty—for a two-person household, it represents an income of about $58,000. While this is certainly an amount you might struggle to live well on, especially if you have a child or other caretaking responsibilities, or chronic medical conditions, or other expensive conditions of a normal life, it represents someone working full time at a little less than double minimum wage.

What about households that actually make minimum wage? Or have only part-time work? Or can't work at all because of disability or age, or caretaking responsibilities? Not surprisingly, it is these households who are most likely to be caught in housing that is unaffordable to them, or "doubled up" in overcrowded housing, or housing with serious health and safety issues, or who are on the verge of or experiencing homelessness. Very often, advocates (correctly, in my view) identify affordability at these levels—say, 30% AMI and below—as the most critical need.

So why don't more programs that create affordable housing offer affordability at these levels?

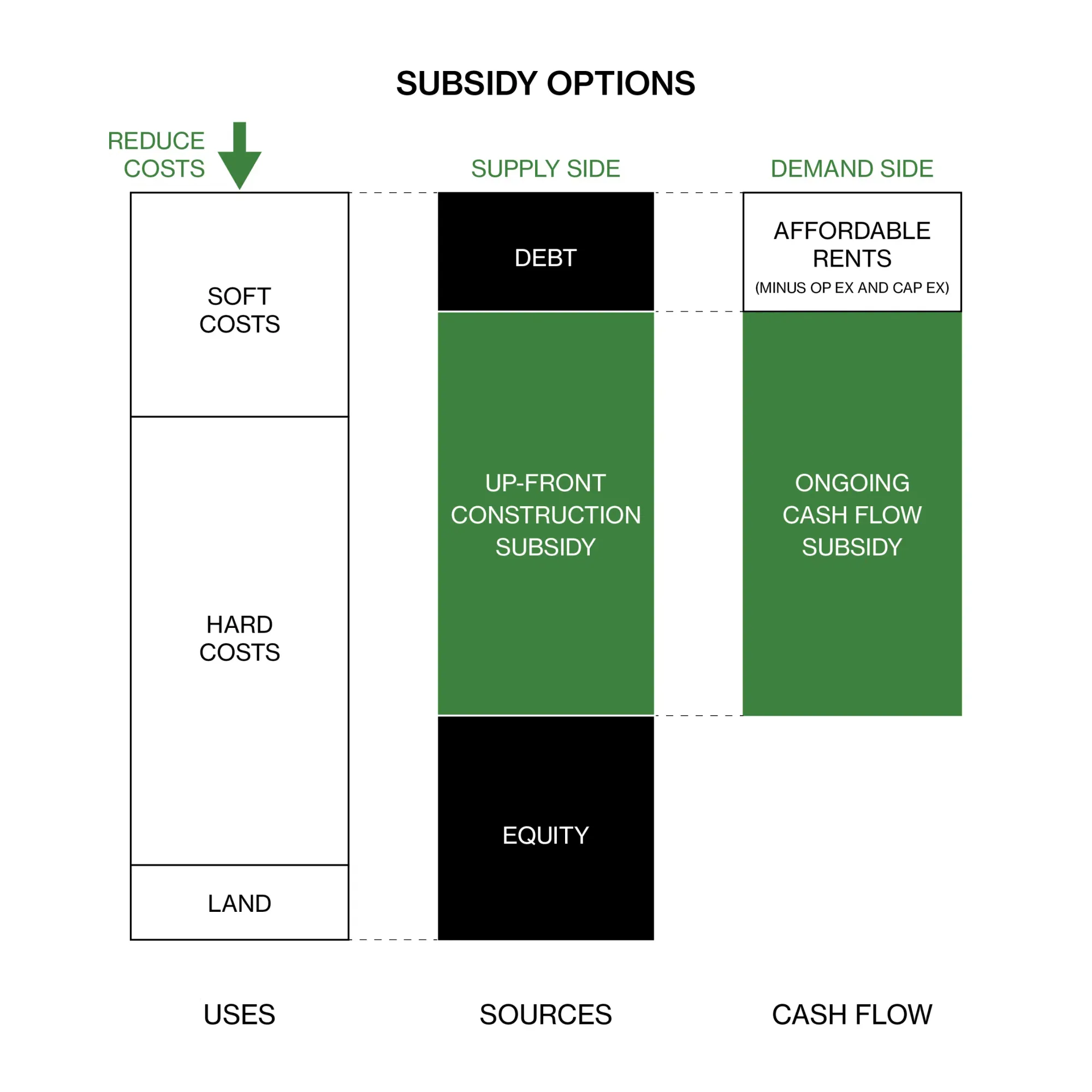

To get at the answer to this question, it's important to understand that basically all affordable housing programs do one of two things: They provide capital subsidy, or they provide rental subsidy. Capital subsidy gets you a building. Rental subsidy gets you deep affordability.

Capital subsidy gets you a building

Let's say you are a market-rate developer, eyeing a piece of land to build on. How do you know how much to pay for it?

Well, first you can figure out how many homes you can build on that land, and how much you think they'll rent for—that'll be your income. Then you can subtract how much you'll need to pay your bank (for your construction loan) and your investors (who also gave you money to build your building). Then you can subtract how much it will cost to operate the building and pay your taxes, and how much money you need in profit for it to be worth spending several years working on this project. Assuming these costs haven't yet eaten up all your projected income, what's left is how much you can afford to pay for the land.

With this example, you can start to see the problem for developers of affordable housing. They start by shrinking their income quite substantially, because they plan to charge less for rent than a market-rate developer. But their cost of construction and operations aren't any lower (in fact they're almost certainly higher), and while they might not make as much profit as a market-rate developer, they still need to pay for several years of their own salaries to actually do the work. What all of this adds up to is that affordable developers simply can't afford to buy the land for the same price that market-rate developers can—which means they're going to get outbid.

In fact, it's worse than that, because in nearly every case, the affordable developer is already in the negative once they've subtracted the cost of a full construction loan and operating costs from their anticipated rental income. In other words, they couldn't afford to build their building and keep it affordable even if the land were free.

Enter government housing programs—specifically, capital programs. Capital programs help cover the cost of building a building to align the costs that the affordable developer is responsible for with the amount of rental income they expect to receive. They might do this through grants, or low-interest loans, or some combination—but the bottom line is they're taking on some of the costs associated with construction (or, in the case of buying a building, purchase and rehab).

So why don't capital programs like LIHTC, or the revolving funds inspired by Montgomery County, MD, and known as Green Social Housing in Chicago, simply cover costs to the point that the affordable developers can charge 30% AMI or less?

The answer is that when you start with 30% AMI rents, just subtracting the cost of operating an apartment building already gets you into negative cash territory. In other words, you could hand an affordable developer the land and then build them a building and charge them nothing for it and they would not be able to afford to keep it in good condition, pay their taxes and utilities, staff, and so on, while only charging 30% AMI rents.

Rental subsidy gets you deep affordability

Enter the government—but this time with rental subsidy programs. Essentially, rental subsidy programs are designed to make up the difference between what a household can afford to pay and what a building owner needs in order to keep their building running—or, in some cases, with what market-rate landlords charge.

Whenever you see more than a handful of deeply affordable homes, there are rental subsidies involved in some form. In LIHTC buildings, they are often Project Based Vouchers or Project Based Rental Assistance from the local public housing authority or directly from HUD. Permanent supportive housing that doesn't receive subsidies from one of those sources may get it from the local Continuum of Care. Public housing gets it in the form of Annual Contribution Contracts, an agreement from HUD to provide a certain level of support in cash every year.

The bottom line: There are effectively zero capital programs—the ones designed to let a public or private affordable developer build or acquire and rehab a building—that create deep affordability. The rental subsidy does that.

This is even true abroad: European-style social housing typically combines capital subsidies that create moderately affordable housing with "housing allowance" payments that allow households that can't pay those costs to make up the difference.

So why do capital subsidy at all?

So if capital subsidy doesn't get you deep affordability, and deep affordability is the greatest need, why do capital subsidy programs at all?

For one thing, capital programs reduce the cost per unit of rental subsidy programs. That is, when an affordable developer's construction mortgage payments are reduced because of capital subsidy, it means they don't need as much rental income—which means they don't need as much in rental subsidy to provide deep affordability. This is a big deal, because while capital subsidies are a one-time investment, rental subsidies need to be paid out continuously every year, and any interruption of subsidy payments threatens to displace or even make homeless the tenants who depend on them. The less that subsidy costs, the easier it is to maintain it (and the more you can do with any given amount of funding).

For another thing, it can be much harder to match rental subsidies with apartments than it might sound. Subsidies come in two main flavors: Tenant-based, meaning the subsidy belongs to a tenant household who can use them in any apartment where they sign a lease; and project-based, meaning the subsidy is attached to an apartment and can be used by any (income-qualified) tenant who signs a lease for it.

Although it's illegal to discriminate against tenants just because they have a rental subsidy, such discrimination is in fact an endemic barrier to using tenant-based subsidies. Furthermore, tenants may struggle to find apartments they can afford, even with the boost of the rental subsidy—especially if they are looking in higher-cost neighborhoods, or need an apartment that's accessible to people with physical disabilities. Fundamentally, the issue with using project-based subsidies are similar: Most market-rate landlords have little financial incentive to sign up to use them, and may have prejudiced ideas about what kinds of tenants would use them. As a result, it can be easiest to use both tenant-based and project-based subsidies in buildings that are owned by mission-driven developers—the ones who need capital subsidies.

In addition, sometimes rental subsidies can only be unlocked by capital subsidy. In particular, public housing authorities receive Annual Contribution Contracts only for units they have built or acquired. Using capital subsidy to get the building is what allows CHA to receive the rental subsidy that creates deep affordability.

Finally, there are all the reasons unrelated to deep affordability, some of which are explored in this post (community development, housing quality, etc).

From each (program) according to its ability

In conclusion, different programs are capable of doing different things. Capital programs, like LIHTC or "social housing" will not on their own be able to create deep affordability. But they can provide the physical homes into which rental subsidy can be sent that does create deep affordability.