Deep v. shallow capital subsidy, or: What is the Montgomery County model's secret sauce?

In a previous post, I wrote about how it's worth separating the way we fund affordable housing into two buckets: Capital subsidy, which helps the government or a mission-oriented third party buy or build a building; and rental subsidy, which makes the homes in a building extra affordable.

In a given project or program, of course, both kinds of subsidy, of course, can be bigger or smaller (often the words used are "deeper" or "shallower"). When rental subsidy is deeper, the effects are fairly straightforward: the program can serve people at lower incomes.

In this post, though, I want to talk about when capital subsidy is deeper—or shallower—and some of the more interesting consequences. In fact, I'd like to propose that one of the things that makes the Montgomery County model of mixed-income publicly controlled housing, sometimes known as "social housing" (or "Green Social Housing" in Chicago), both distinctive and important in the U.S. context is that uses shallow capital subsidy. This sounds underwhelming, but it ends up requiring a series of other choices that make it ultimately a very important contribution to the long-term future of housing affordability.

You can think of the purpose of capital subsidy as reducing the size of a building's construction or acquisition loan until it's small enough that the building's lower, affordable rents can cover the debt payments. The math is really no different than a young homebuyer whose parents make an extra-large down payment so that the mortgage is small enough for their kid to afford the monthly payments. Or, as I wrote in the last post:

[I]n nearly every case, the affordable developer is already in the negative once they've subtracted the cost of a full construction loan and operating costs from their anticipated rental income. In other words, they couldn't afford to build their building and keep it affordable even if the land were free.

Enter government housing programs—specifically, capital programs. Capital programs help cover the cost of building a building to align the costs that the affordable developer is responsible for with the amount of rental income they expect to receive. They might do this through grants, or low-interest loans, or some combination—but the bottom line is they're taking on some of the costs associated with construction (or, in the case of buying a building, purchase and rehab).

"Deep" capital subsidy: More immediate affordability, but also more precarity

I'm not aware of a broadly accepted formal definition of "deep" or "shallow" capital subsidy. In principle, the "deepest" capital subsidy possible would be to pay for the entire construction or purchase price and rehab cost, leaving the building with no mortgage to pay at all. Most new affordable rental housing doesn't reach this level, but it is much closer to that than to the typical mortgage cost of a market-rate development: While market-rate buildings often are able to take on loans that are 50-75 percent of the total cost of construction (with the rest coming from equity investors and the developers themselves), LIHTC projects in Chicago are often within spitting distance of 10 percent. (Note that I'm not counting loans with balloon payments, which is often how public loans are structured, because those don't require the same kind of regular payments that necessitate more rental income from the building.)

When you only have to pay for a mortgage that covers 10% of your construction cost, you can set much lower rents across the building, of course. But the other side of that coin is that when, in a few decades, you need to take out a significant loan to replace the roof, or the elevators, or so on, you are in a bind: By taking advantage of the deep capital subsidy you started with, you set your rents too low to pay for that kind of heavy-duty maintenance twenty or thirty years after construction.

Not coincidentally, this is also when the affordability restrictions of LIHTC tend to give way. The "temporary" nature of LIHTC affordability is not just a regulatory shortcoming, then: In a way, it's a product of its financial structure. After 30 years, many LIHTC buildings need to either raise rents to pay for major rehab, or they need another infusion of capital subsidy—a "preservation" deal. (Contrast this with ~permanently affordable public housing, which receives a per-unit capital subsidy every year to make up for the limited rents public housing authorities receive, even when counting the annual per-unit rental subsidy. Of course, these capital subsidies are woefully inadequate, which in recent decades has led public housing authorities to also seek "preservation" deals.)

In short: Deep subsidies help allow for more and deeper affordability right away, but that deep affordability leaves affordable housing vulnerable to the "preservation" cycle, in which significant capital funds must be used to avoid the loss of affordability every few decades. Obviously this leads both to potential precarity for any given affordable building, but also to a situation where a very large proportion of public capital subsidy in any given year is spent on existing, rather than new, affordable housing.

"Shallow" capital subsidy: Less immediate affordability, but more staying (and growing) power

The Montgomery County model, on the other hand, uses what I would call "shallow" capital subsidies. The portion of construction cost paid for by loans is similar to that of market-rate buildings, or sometimes even higher.

Rather than grants or balloon-payment loans, the primary capital subsidy in the Montgomery County model comes from a) below-market interest rates on the main loan, and b) replacing very expensive private equity that makes up 15-30 percent of market-rate development with a low- to no-interest public revolving fund.

What this means is that unlike most LIHTC developments, buildings using this model need to have rents that are high enough to cover meaningful debt payments, even if they are lower than market-rate. That's why this is an inherently mixed-income model—it needs market-rate rents on many of the apartments to make those debt payments. (Compare this to, eg, mixed-income public housing, which is mixed-income as a policy choice: Public housing, with its ongoing capital and rental subsidy, generally does not need any market-rate rents to support itself.)

But it also means that when Montgomery County-style buildings reach an age where they need significant maintenance and repairs, they are able to pay for it without a new infusion of preservation capital subsidy, or raising their rents. As a result, the flip side of these buildings being "inherently" mixed-income is that their affordability is "inherently" permanent—as long as their ownership is mission-oriented, which is why some kind of public or quasi-public control is an important feature of many instances of this model.

And in fact the benefits go beyond that. Because once a Montgomery County-style building has paid down a significant portion of its construction debt, it will find itself with an increasing surplus between the amount of rental income it receives and what it needs to be able to support maintenance. With that surplus, it can add more affordability. (Montgomery County has in fact added deeper affordability to buildings once their overall cash flow allowed for it.)

It can also pull more funds out of the building—either directly in annual cash flow, or through a loan backed by the equity in the building. With those funds, it can purchase or build more mixed-income buildings, which then eventually create more surplus to invest in more construction or acquisition...and so on. (Again, this is something Montgomery County has already done with their mixed-income buildings.)

This is on top of the fact that the funds initially invested in the building by the revolving loan fund have come back and been used in other projects, not something that can really happen with deep capital subsidy models. Finally, the public funds that would have been used for a preservation deal at year 30 in a deep capital subsidy model is instead also spent on creating or buying new mixed-income housing.

To make a strained and mixed metaphor, the deep capital subsidy model is like a fire that burns hot (more affordability) but periodically needs to be supplied with new fuel (money) lest the fire burn itself out. The shallow capital subsidy model is like a snowball gathering more snow as it rolls downhill: It may be small at first but it keeps growing and growing under its own power.

The shallow subsidy model is a recipe for a larger, stable affordable housing stock

To be clear, none of this is a critique of other models, which we still need—it's an argument for supplementing, rather than replacing, programs like LIHTC. And, of course, it remains true that neither LIHTC nor Montgomery County-style programs can provide affordability for, say, minimum wage earners, or those on fixed incomes, without rental subsidies as well.

Plus, if I had a magic wand, I would simply wish for a federal government that cared enough about people to invest more in housing, and the sorts of tradeoffs I've described in this post would become less relevant. (Though not irrelevant, as the cost of maintaining a much larger stock of deep-capital-subsidy type housing is not a matter of incremental funding increases, but quite substantial ones.)

But in the current reality, how to make housing that is priced to people's ability to pay rather than to the market a meaningful portion of all housing in the face of stagnant or falling public resources is a pretty important question. The Montgomery County model of mixed-income, shallow capital subsidy housing is, in my opinion, the most promising answer.

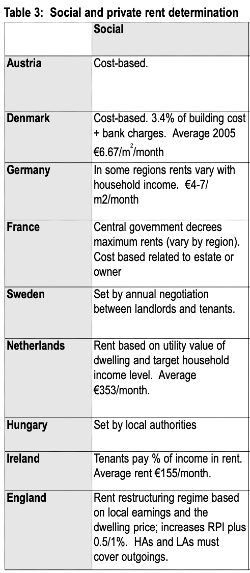

Importantly, this is also how many other places with large affordable or "social" sectors in housing have accomplished that. European countries like Austria, Denmark, and France have non-market housing sectors where rents are often based on the building's operations costs.

The kinds of programs launched by Montgomery County, Atlanta, Seattle, or Chicago in recent years won't revolutionize housing overnight. But they stand a good chance to set us on a path to a better future.